The current female representative of the world-renowned bespoke shoemakers is Emiko Matsuda, who came out of Foster & Son to start her own business. I didn’t realise there was one so close to us.

Take a look at her story together.

Please introduce yourself.

My name is Emi LIAO (LIAO Xinci), I am 31 years old from Taiwan.

How did you get into dress shoes? And how did you get into the industry?

My connection with dress shoes is quite deep. My uncle opened a dress shoe factory in Taicang, Jiangsu Province in the early days, and my father was in the management of my uncle’s shoe factory, so when I was young, I would go to the factory during the summer and winter holidays.

It was in my third year of college that I really started to learn more about shoes. I studied at the Department of Social Work at Chung Shan Medical University in Taiwan, but considering that my personality might not be very suitable for the social work field, my father suggested that I study shoe making, and that’s how I got into the shoe making profession.

Is bespoke shoemaker your initial plan? Or do you work in RTW or some other form first?

When I first entered the industry, I didn’t set out to be a bespoke shoemaker. I started out hoping to learn some professional knowledge about shoes, so that in the future I could become a manager of a shoe factory, like my father, who understands the process of shoe making, checks the quality, and ensures that the appearance is exquisite.

Later on, when I learnt to make shoes by hand, I gradually realised that it is not a technique anymore, but a kind of artistic inheritance and accumulation, where every step is an art and an accumulation and inheritance of experience.

Based on the fact that it is everyone’s responsibility to protect beautiful things, I gradually established my hope to become a bespoke shoemaker.

What was the learning experience?

In fact, the learning process has not changed much.

At first, I planned to stay in Italy for one year, but then I didn’t expect to stay for three and a half years and almost four years. If not for the visa problem, I might stay for a longer period of time.

No matter whether it’s in terms of craftsmanship or lifestyle, I think I’ve already been accustomed to the dashing style of the Italian people.

Why did you choose Italy over the UK to study shoemaking?

The reason for choosing Italy was simple: I liked to read Dan Brown’s novels at that time, and the scenes in his novels were mainly set in Italy, so I wanted to learn a new language, so the only choice I made at the beginning was Italy.

Can you tell us about your master?

When I first arrived in Italy, I studied at the Accademia Riaci in Florence.

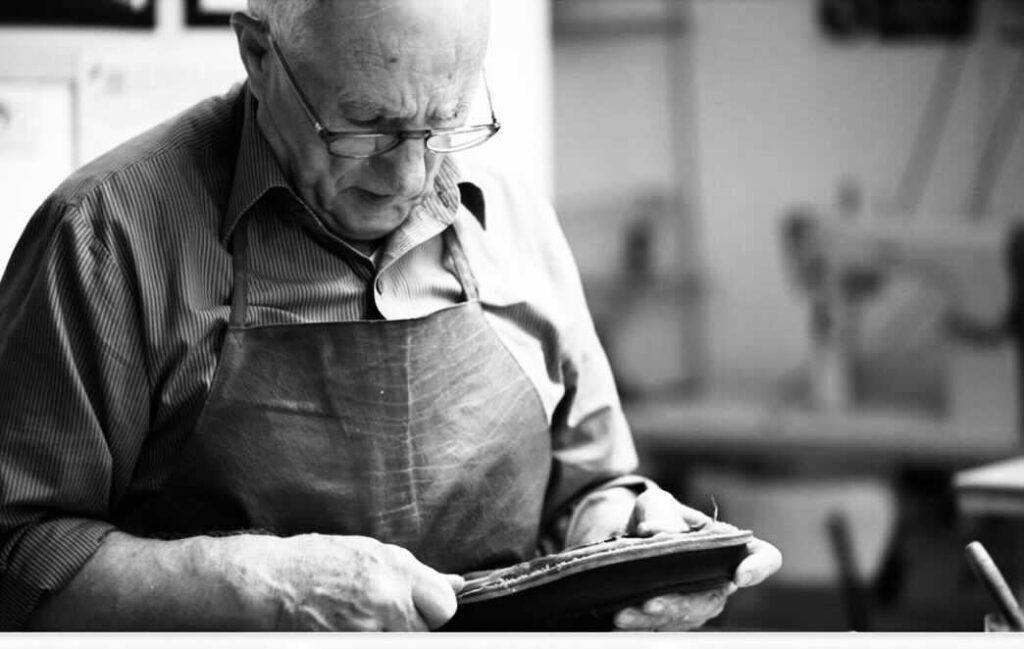

The teacher is an 80-year-old Italian shoemaker, Angelo Imperatrice, who is well known in Florence.

Although Angelo is a veteran shoemaker, his craftsmanship is a bit wild and spontaneous due to his romantic nature.

At the school, there was also a Japanese teacher, Mr Masachika Morita, who was undoubtedly the most important person on my path to shoemaking.

Mr Morita worked for Roberto Ugonini and Maninna.

Adept at the fusion of craftsmanship, he has a good grasp of the balance between the strong uniqueness of Italy and the rigour of the Yamato nation, and the unique line design can often be seen in his works, which is frank but not without elegance.

During my studies, apart from teaching me the knowledge and techniques of shoemaking, I was most influenced by Mr Morita’s comfort and open-mindedness.

He once told me : “There must be many people who are better than you in terms of craftsmanship, but there is no way to imitate the style. There are so many great shoemakers in the world who have first-rate skills, but when their craftsmanship reaches the extreme, what remains is the presentation of personal style, and personal style is actually the internalisation of the way of life, and what kind of a person you are, the shoes that you make will tell you, and you need to know how to live first if you want to do well in shoes. If you want to make good shoes, you have to know how to live first.”

What is unique about Italian shoemaking and aesthetics?

I don’t think it’s possible to separate Italian craftsmanship from aesthetics; Italian craftsmanship is aesthetically pleasing in itself.

The aesthetics of Italian-style craftsmanship, embodied in the post-Renaissance aesthetic, is the pursuit of overall harmony, stability, and symmetry, and its aesthetics is embodied in the perseverance and inheritance of centuries of craftsmanship.

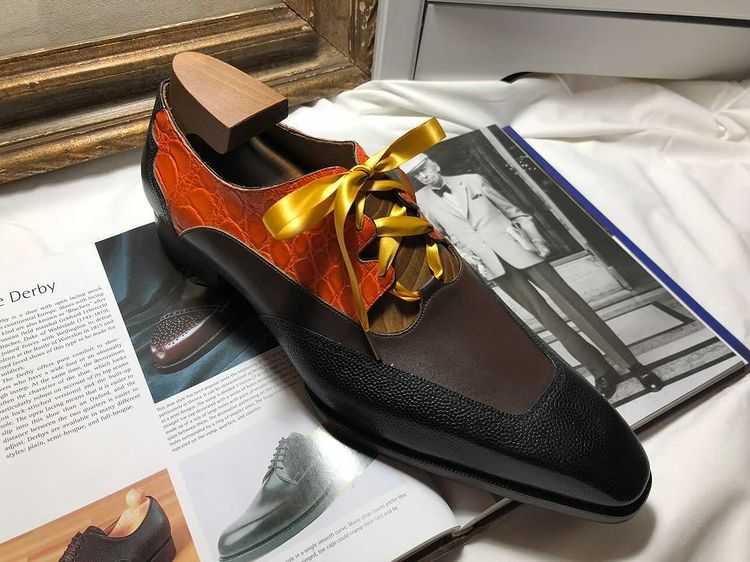

A pair of shoes made in Italy has a unique combination of Italian style and comfort.

Comfort is the most important thing for a pair of shoes, while aesthetics is an indispensable element in Italy.

The innate Italian sense of aesthetics and traditional craftsmanship combine perfectly, and it is only when both exist at the same time that Italian shoemaking becomes the ultimate and existential value.

When I was studying in Florence, I loved visiting Reberto Ugonini’s shoe shop after school because his shoes were the perfect template for Italian craftsmanship: small square toes, bright lines, full colours, and most importantly: wearable!

Even after centuries of tradition, Italian craftsmanship has been preserved and is still alive and well. This is why, even in the face of the equally powerful England and France, and later Japan, Italian craftsmanship still has an absolute place in the world.

I’ve always liked a Japanese master Akira Tani who worked at Stefano Bemer before, he left bemer and set up his own studio also in Florence, and knew ZHAO Ruoda (a Chinese bespoke shoemaker who studied in Stefano Bemer) very well.

When did you return to Taiwan to start your own practice?

After finishing three and a half years of study in May 2018, I returned to Taiwan and spent six months preparing my studio.

At first, I didn’t take orders, I just made them for my friends and family, and this lasted for about half a year before I formally accepted customers.

What is your housestyle?

Although many customers say that they can see the Italian style in my shoes, I feel that I have not yet been able to create my own house style like Yohei Fukuda, who is a god in my heart, and I have travelled to Japan to visit Mr. Fukuda in person, and Mr. Fukuda has encouraged me to persevere. Mr Fukuda encouraged me to persevere and one day I will be able to find my own house style that no one else can imitate.

Having served most of the customers so far, the most satisfying part is probably in the communication with the customers, to understand and satisfy their needs as much as possible, and then provide more professional advice to make a pair of comfortable, suitable and special shoes.

What’s the next step?

I am a Freshman on this century-old road of shoemaking, and I am still looking up to every shoemaker’s predecessors to find my way. The deeper I learn about shoemaking, the more I understand my own inadequacies and insignificance, so I can only be more humble and work harder to learn, and I hope to embark on a journey of visiting excellent shoemakers all over the world again on the day when the epidemic subsides and the blockade is lifted.

I don’t like to think about things that are too far away or too ambitious, because I once read this: “When your talent can’t support your ambition, you should calm down and learn; when your ability can’t control your goal, you should calm down and practice. The dream is not to be impatient, but to precipitate and accumulate, only to spell out the beauty, not to wait for the splendour.”

您好。请问Emi的工坊/品牌具体叫什么呢?

她目前在John Lobb St James工作,可能要等她学艺完成才会重新执业了。